Note: Excerpted from Solution-Focused School Counseling: The Missing Manual

by Russ Sabella, Ph.D.

Solution-focused brief counseling is a systemic approach designed to include all stakeholders. Early on, in the 1990s when I was experimenting with how SFBC worked with children in a school setting, I stumbled onto a bit of a glitch. I was getting referrals from both teachers and parents who were highly distraught, “hanging on for dear life” because the student was misbehaving so badly. Once again, I’m reminded of Ethan, the student who was dealing with an anger management problem (p. 13). Remember that, after only a short time, I was excited to celebrate with his mom the achievements that he was making in class.

But when I approached Ethan’s teachers or his mom (the very parent who referred him to me) to share the good news, they minimized the progress, which is not at all what I expected. They would say things like, “You don’t know this child like I know this child, he’ll be back to his old ways in no time.” Even Mom continued to hold her breath as she anticipated her son’s next outburst. They seemed to perceive the student’s progress as an exception and continued to expect bad behavior. I was caught off guard and truly surprised because I was expecting some relief, hope, and maybe a little bit of gratitude.

Why would a struggling teacher or parent not be as excited as I was about how much progress the child was making? My colleagues and I struggled to find plausible explanations, and we considered several possibilities. First, could it be that the teacher or parent was uncomfortable with change? Could it be that they knew how to deal with a misbehaving child, perhaps getting accustomed to the situation, and did not want to adjust to a new way of interacting? Second, could it be they just simply did not believe that such positive change over a brief period of time was real? Perhaps they thought that true change could only be accomplished with Herculean efforts over a period of time commensurate with the problem? That is, if a child misbehaved over a whole year, wouldn’t it take at least a few months to get back on track? Third, and probably most plausible, could it be that the parent or teacher was embarrassed? As we thought through the scenarios, this third reason began making more sense. If a teacher or parent had been trying to help a child change for the better over months or years and could not accomplish this, and you, the counselor, could do it in a matter of weeks, might they feel incompetent or a bit abashed?

In response to this issue, I developed the following process to minimize these possibilities while enhancing the systemic nature of the solution-focused approach. In this way, all parties get credit for their contribution. Here’s how it works:

Step 1: First, acknowledge and praise the work that the teacher or parent has already done. In a way, this means stroking their ego or at least recognizing their efforts and dedication to the child. This is a time for cheerleading. You might say, “You have worked so hard with this child/student for a long time. I am amazed at how you have hung in there. You really care about their future!”

Step 2: Minimize your potential impact and emphasize teamwork. Let them know, “I’m not sure that there is anything I can do that you have not done already. Perhaps together we might be able to make a small change for the better.”

Step 3: This next step is what I call issuing a BOLO or Be On the LookOut, a term I adopted from law enforcement. Ask them, “Please be my eyes and ears in the classroom or at home. If you see any sign that the child is more on track, doing the things we hope for, please let me know. This includes any sign at all. If they bring their pencil to school when they usually do not, I need to know that. In fact, when I see you again, I will ask you what you noticed that might be a sign that what we are doing is working.”

The impact of this step is that we now have teachers, parents, and perhaps other stakeholders involved in the intervention and looking for signs of progress. What we know from this model is that you get more of what you look for, and when teachers and parents look for signs of improvement, they are more likely to find them. My colleagues and I also discovered that, in turn, students notice adults giving them more attention when they are better behaved, making responsible decisions, or achieving. Consequently, even before the next solution-focused meeting, you may see progress just because everyone is “on the lookout” for signs of improvement.

Step 4: When progress is detected, conduct a solution-focused interview with each person. Ask the teacher and parent, “What do you think you did in the classroom or at home that would help explain how this child is improving? How did you do that, even though it was sometimes frustrating or difficult? How is your life better because they are more on track?” Then conduct a follow-up EARS meeting with the student and remember to detail, mind map, minefield, cheerlead, amplify, and scale.

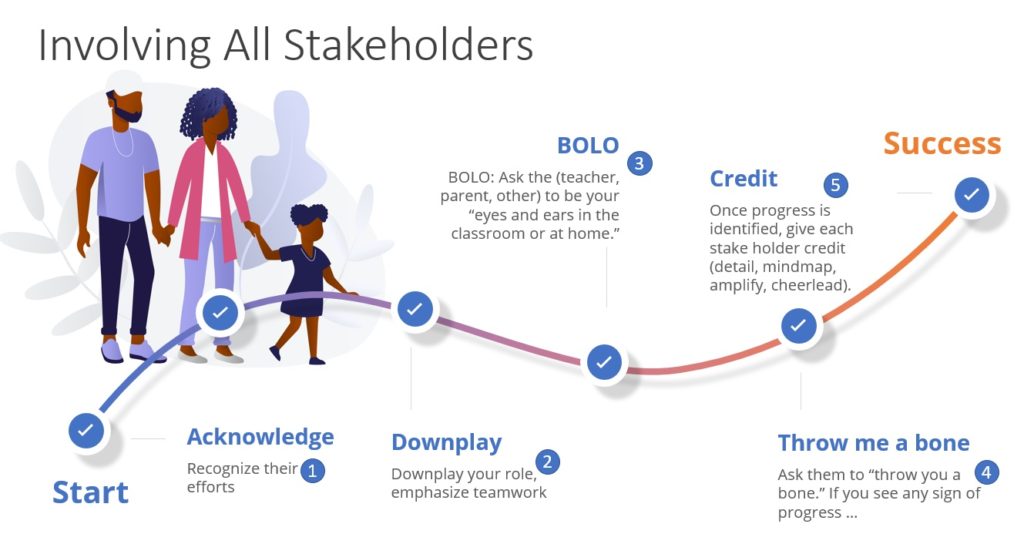

With these four steps, everyone is involved, included, and gets credit for the progress (see Figure 6). They also feel empowered and encouraged about the future.

Figure 6: Involving all Stakeholders

Another way to visualize the process:

Before we move ahead, I want to emphasize one more tip and caveat involving step 3—issuing the BOLO. In this step, it’s important to emphasize to the teacher or parent that you are interested in any sign of progress, no matter how small. Improvement can include what they did or what they could have done, although refrained from doing. For example, I say, “If the student normally curses you out in the first ten minutes of class and this time, they waited 20 minutes, that’s progress (about 100% progress, indeed)! I need to know about that.”

I know that I mentioned this in the section on cheerleading, but it is worth a reminder, some adults will get annoyed with you when you do this. You may even get some “push back” as I have, mainly when the progress entails behaviors that they already expect. I had a teacher once tell me that I was “blowing sunshine up a student’s bottom” (not her exact words) because I was making such a big deal about them doing 25% of their homework (even though, on average, they were doing much less than that). I explained that I understand that students are responsible for the minimum levels of productivity and discipline. Some students are simply not close to meeting basic expectations. Waiting until the student meets the minimum requirements to cheerlead them has not worked. Instead, when a student begins to make progress, even in small increments toward minimum standards, we need to cheerlead those efforts and decisions. Alternatively, we can continue doing what we’ve always done while expecting a better outcome. In other words, settle for insanity.

For more information about the book, check out:

https://schoolcounselor.com/professional-development/themissingmanual/

Dr. Russell A. Sabella is currently a Professor in the Department of Counseling in the College of Education, Florida Gulf Coast University and President of Sabella & Associates.

Dr. Russell A. Sabella is currently a Professor in the Department of Counseling in the College of Education, Florida Gulf Coast University and President of Sabella & Associates.